Best Practices on Communicating Load Requirements

When designing a building, one of the most critical elements engineers need to manage is communicating structural loading requirements. This communication between the engineer and the joist manufacturer can make or break the success of the project. While there are several methods to specify loads, the focus of this blog is on two common ones: Total Over Live Load (TL/LL) and Standard Designation (SD). We'll explore their differences, advantages, and when to use each approach—so let's dive in!

TOTAL OVER LIVE LOAD (TL/LL):

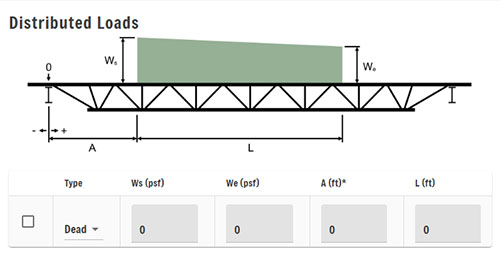

When using the TL/LL method, engineers specify two key components: total load (dead load plus live load) and live load separately. This allows the joist manufacturer to optimize the joist design based on actual conditions, ensuring that every load (uniform, point, non-uniform) is accounted for.

Why Engineers Like TL/LL:

- Transparency: You get a clear view of assumptions and calculations.

- Design Optimization: Joist manufacturers can tailor the design to the exact loads, potentially saving material and cost.

- Flexibility: It’s easier to specify special cases like drift loads and point loads.

In practice, an engineer calculates the dead load (building structure, fixtures, etc.) and live load (occupants, snow, wind, etc.) based on building codes. They can then add any other specific load needs, like equipment. The joist manufacturer designs the joist to withstand the worst-case scenario. Simple, right?

STANDARD DESIGNATION (SD):

The Standard Designation method is more of a "plug-and-play" approach. Engineers select a standard joist size from the Steel Joist Institute (SJI) catalog. For example, a joist labeled 16K3 comes with predefined maximum load values for its depth and span.

Benefits of SD:

- Simplicity: Quick to specify, especially for uniform loads.

- Proven Designs: These tables are based on common loading conditions.

Drawbacks of SD:

- Limited Customization: It’s like a black box—you won’t know if the standard designation is perfectly suited for your project, especially if you have unusual loads.

- Material Waste: Because the tables round up load requirements, you might end up using more steel than necessary.

COMBINING STANDARD DESIGNATION + SPECIAL LOADING (SP)

For projects with special load requirements (like large mechanical units), you can add an "SP" designation to a standard joist size, for example: 16K3 SP. This method accommodates unique load cases while still using standard joist sizes.

Special loading conditions:

- Large point loads (ex: mechanical units)

- Non-uniform loads (ex: drift loading)

- Axial loads

- Tight deflection criteria

Advantages over pure standard designations:

- Accommodates special loads while still allowing use of standard joist sizes

- Simplified communication of loading requirements to joist manufacturer

Disadvantages compared to TL/LL:

- Still lacks full transparency of design assumptions

- May result in unneeded extra steel if special loading is conservative

- Coordination required to ensure joist manufacturer designs for worst case of standard OR special loads

HOW TOTAL OVER LIVE IS USED TO CREATE A STANDARD DESIGNATION

Many engineers calculate TL/LL loads and then look for a matching standard joist. While this sounds practical, it often leads to over-design and unnecessary material use. For example, if your total load is 330 plf (pounds per linear foot), you’ll look up the closest standard size. But the standard size might be overkill, leading to higher costs and potential inefficiencies.

Pro Tip: Let the joist manufacturer design the joist based on your TL/LL specification. It saves time and optimizes material usage.

WHEN TO USE TL/LL VS. STANDARD DESIGNATION

In most cases, TL/LL is your best bet. It offers more flexibility, better cost control, and ensures you’re not wasting resources on unnecessary steel.

That said, standard designation is still useful when you have uniform loads, and/or your project is simple, with short spans (under 550 pounds per linear foot) and no special load requirements. Standard designation is also suitable when the engineer wants extra buffer for future loads and is okay with the extra cost.

Standard + SP is a solid choice for projects with mostly uniform loads, but a few special loading conditions. Standard + SP is also smart when load location is uncertain. Engineers are often challenged by not knowing exactly where loads will be placed, whether initially or during the life of the structure. This is most common for mechanical HVAC equipment or process equipment.

Consider using Standard + SP if the engineer prefers standard sizes and special loading. Common use cases include warehouses with heavy point loads from material handling equipment, and school gymnasiums with large mechanical units and tight deflection limits.

BEST PRACTICES FOR COMPLEX TL/LL LOADING:

- Snow Drift Loads: Include clear instructions in your drawings for applying snow drift loads on top of TL/LL loads. Provide a load map to specify where the drift occurs.

- Joist and Girder Coordination: While joist software can handle uniform and trapezoidal loads, it’s best for the design professional to specify additional point and drift loads on girders.

- Use "Add Loads": If the exact location of point loads (e.g., HVAC units) isn't known, specify "Add Loads." This accounts for moving point loads, ensuring the joist has extra capacity without the need for costly redesigns later. The “Add Load” in essence creates a small constant shear/constant moment capacity within the joists, which alleviates the need to go to a full-blown KCS design. “Add Loads” can be defined by load type as well.

- Bend Checks: When point loads aren’t placed at panel points, they can cause secondary bending in joist chords. A common solution is to install extra strut webs to handle these loads. However, if many struts are needed, it’s better to use "Bend Checks." A Bend Check applies a load to test how the joist chords handle bending between panel points under normal design forces. This check can be applied to either the top or bottom chord. Use these checks carefully, as they can increase costs, especially for bottom chords. Judicious use of “Bend Checks” in conjunction with “Add Loads” is a good way to add resilience to the joist design and mitigate against the uncertainty of load locations.

- Group Similar Joists: Instead of creating several custom joist designs for minor spacing differences (e.g., a few inches), it's more efficient to group similar joists under the same TL/LL design. Small variations don’t justify separate designs, and trying to optimize every joist can complicate manufacturing and installation. The best approach is for designers to combine joists with uniform loading into larger groups. Joist manufacturers often do this for snow drift loads as well, reducing the number of unique designs needed and streamlining the process.

These practices simplify complex loading situations, reduce costs, and add resilience to the overall design.

In the end, how you communicate loading can significantly impact your project’s efficiency and cost. The total over live load method generally provides more transparency and flexibility, making it easier for everyone involved to get things right. Standard designations have their place, but for most projects, TL/LL should be your go-to. Feel free to reach out to a Vulcraft representative for more information, or for help with communicating loading requirements.

About the author

Gerald McKenzie, SE (UT), PE (ME, DE, TN) is a Design Engineer in Vulcraft's Indiana division. He has 20 years of experience as a specifying engineer of record, with 13 years as part owner in a consulting engineering firm in the Salt Lake City area. He also has five years of project management experience for a commercial construction company.